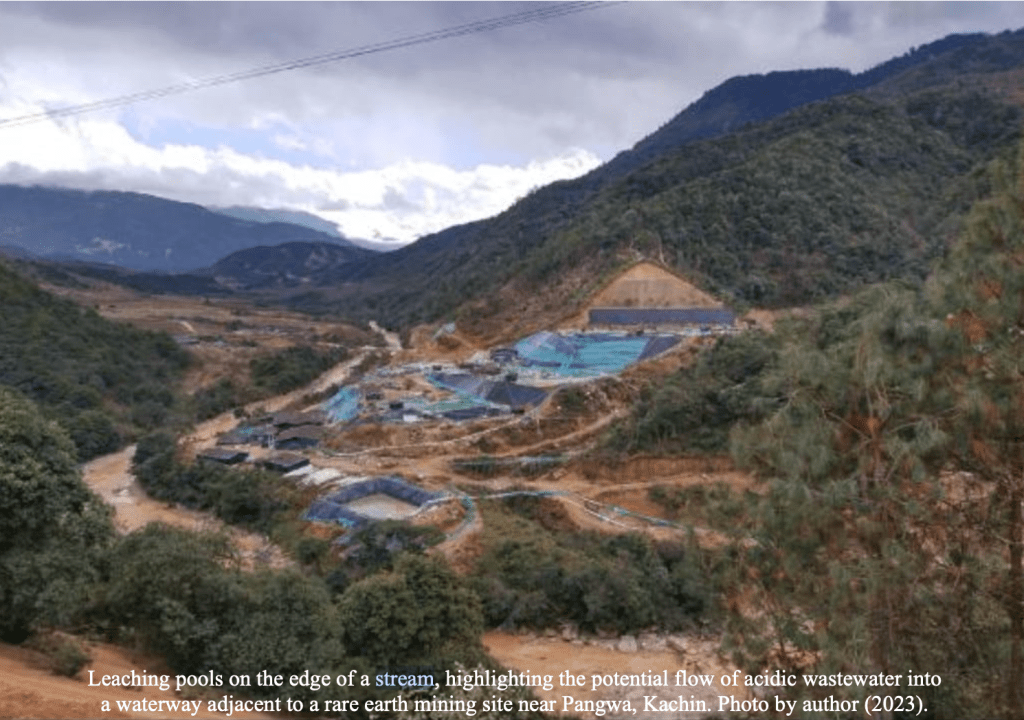

Sidney Mintz* once wrote how the links between a spoon of sugar in the tea of an English worker, a plantation in the Caribbean, and the rise of colonialism and capitalism were like yet another chorus of the children’s song ‘dem bones’: the leg bone’s connected to the knee bone, the knee bone’s connected to the thigh bone, the thigh bone’s connected to the hip bone… Such links have only multiplied and thickened with time. Today’s global transition to a clean-energy economy (think electric cars and wind turbine generators) requires high-performance permanent magnets. These components need “rare earths”, minerals like dysprosium and terbium. The knee bone shakes all the way down to the ankle bone, the foot bone, and the toe bone…. and from a electric car on my street we go all the way to landscapes ravaged by rare earth mining in a country torn by civil war – Kachin state, Myanmar, right on the border with China.

Thi Thi Han’s thesis explores the dark side of clean energy. She asks why rare earths are framed as “critical minerals” (which we need to access at all costs) as opposed to being framed as “conflict minerals” (whose exploitation is intimately linked to violent resource frontiers, which need to be regulated)? She does this with gutsy, engaged, and reflexive fieldwork in the border areas of Kachin state, and just yesterday defended it in a public defence here at the University of Lausanne. Congratulations to Thi Thi!

Her PhD thesis, entitled “The Paradox of Just Transitions: Rare Earth Mining in Myanmar’s Civil War”, is in monographic form and is motivated by a strong concern for her homeland. Thi Thi Han investigates how the insatiable global demand for rare earths (in part for use in energy transitions), and the dominance of this market by China, leads to unfettered exploitation of these minerals in the borderlands of Myanmar’s civil war. Her work focuses on Kachin province and addresses the issue at three scales: the local scale of impacts on lives and the environment, the regional scale of territory and geopolitics, and the global scale of supply-chain governance (or notably, the lack thereof).

The topic of rare earth mining is extremely political (of global geopolitical and economic importance, frequently in front page media these days), and doubly so in a volatile border zone of Myanmar where actors include the authoritarian post-coup government, the national military, diverse armed militias, and Chinese investors. Accessing the field required finessing encounters with authorities and careful attention to security and ethical concerns for all involved. This led to more reliance on anecdotal, descriptive, adaptive, and virtual fieldwork. Thi Thi has nonetheless crafted a very productive and convincing thesis out of this material.

The empirical chapters make several original contributions: documenting the consequences of the rare earth mining boom in Kachin on the lived environments and livelihoods of local residents (Ch 5 and 6); analysing in detail the constellations of actors and mechanisms by which they access and control mining resources in this frontier zone across four periods since the 2011 democratic transition (Ch 7); and demonstrating why international governance of mining has failed to regulate what is demonstrably a flagship case of conflict minerals (Ch 8).

In my opinion, the two strongest contributions from the thesis are: First, a methodology chapter (Ch 4) that reflects cogently on the challenges of fieldwork in an authoritarian state and conflict zones on contested topics. Illustrated with anecdotes, Thi Thi succeeds in making a case for the value of exploratory, best-you-can-do-ethically-and-practically field research, given the extraordinary circumstances. Second, her global governance chapter (Ch 8) – drawing on interviews with industry experts and observations of international negotiations – clearly outlines the tensions between two different ‘framings’ of rare earths: as ‘conflict minerals’ (to be avoided) and as ‘critical minerals’ (to be obtained at all costs), and how the latter has so far dominated, prolonging the injustices (and conflict-related governance) of uncontrolled mining in Kachin so amply documented in the previous chapters.

Funded by a well-merited, competitive Swiss Government Excellence Scholarship, Thi Thi has done an excellent job and we will be sad to see her move on to her next adventures.

*Sidney Mintz (1985) Sweetness and Power: the Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin. see page 214.

I am glad to see that Thi Thi has finished what looks to be a fascinating and much needed thesis!