I’ve finally received my copy of the new edited book Conservation and Environmental Management in Madagascar, edited by Ivan Scales of Cambridge University. This will be a fantastic resource for scholars of Madagascar new and old, as well as more broadly. It includes chapters on a full array of topics: on biodiversity, palaeoecology, and archaeology, on the measurement and causes of deforestation, on environmental politics, policies, programs, and projects, and on different economic development-and-conservation solutions, often (but not always) from a political ecology perspective, broadly construed.

Highlights for me in the book – which also has two of my own chapters – include:

• A clear, concise, and useful summary of current knowledge and ideas about the origins and status of Madagascar’s biodiversity, including continental drift and contemporary biogeography (by Jörg Ganzhorn, Lucienne Wilmé, and Jean-Luc Mercier)

• A masterful overview of the evidence for human arrival (multiple times, from different places) and human impact on the island (in terms of vegetation change and megafauna extinctions). It includes evidence that stone-age peoples, perhaps the “vazimba” of lore, were on the island 4000 years ago. The chapter is by Bob Dewar, who so sadly passed away last year. He and his wife Alison Richard were always so kind and generous with their advice to me on Madagascar beginning twenty years ago when I was at Yale.

• A clear, strong, and cogent critique of the different community-based natural resource management (CBRNM) approaches that have been tried on the island, including GELOSE and GCF, including the observation that community-based agreements around lake and marine resources may paint a more successful picture than those in forest environments (by Jacques Pollini, Neal Hockley, Frank Muttenzer, and Bruno Ramamonjisoa)

• A pair of chapters that explore the last decade’s rapid expansion of protected areas (under the “Durban Vision”) from two very different yet complementary perspectives. Catherine Corson investigates the political sausage factory of negotiations among multiple actors and different scales that shaped the park expansion program, and zooms in on cases where limited consultations took place and which catalysed increased deforestation. She concludes that it would have been better to focus on making the existing park system more effective. In turn, Malika Virah-Sawmy, Charlie Gardner, and Anitry Ratsifandrihamanana review the history of protected areas in Madagascar, place the expansion program into the context of the IUCN protected areas categories, and report constructively on struggles with participatory governance structures in two new protected areas in the south of the island.

• Very useful and critical overviews of several important economic activities touted as solutions for the biodiversity crisis: tourism (by Ivan Scales), bioprospecting (by Ben Neimark and Laura Tilghman), and market-based approaches such as payments for environmental services (PES) and REDD (by Laura Brimont and Cécile Bidaud).

• Jeff Kaufmann points out how Malagasy cultural terms like “fady” (taboo) and “dina” (community pacts) have particular histories and cultural contexts and problematizes their appropriation by conservation actors.

There are more chapters – the book’s capable editor Ivan Scales adeptly fills a few gaps with his critical reviews of deforestation causes and of the history of the Malagasy state.

And I have two chapters in the book. The first, with lead author Bill McConnell of Michigan State University, investigates the measurement of deforestation on the island, pointing out a variety of stumbling blocks and questioning the persistence of exaggerated, indefensible statistics (see separate blog post).

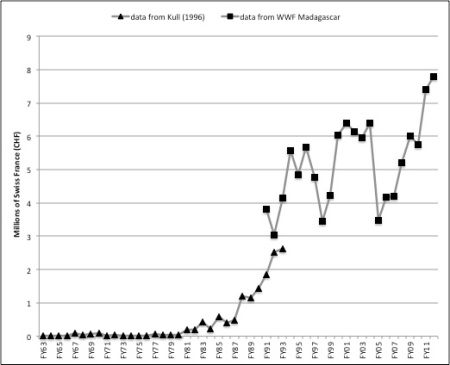

The second, entitled “The roots, persistence, and character of Madagascar’s conservation boom”, reviews 50 years of conservation history on the island. I try to explain why there was such a growth in conservation activity around 1990, and to trace the swings and trends that have shaped the major programs that followed under the National Environmental Action Plan’s three stages, PE1, PE2, and PE3. The most telling part of the article is this figure (below), which shows WWF expenditure on the island.

Figure 7.1 Annual expenditures by WWF in Madagascar – currently celebrating 50 years of work on the island – are illustrative of the conservation boom and its persistence.

Notes: WWF, while the oldest and largest, is only one of many actors investing in conservation on the island. Note also that strong WWF expenditures in the past few years, since the 2009 political crisis, reflect its ability to seek alternative funding through its global network at a time when much traditional bilateral and multilateral donor environmental funding has dried up. Many other conservation actors have struggled to maintain funding and activities in the current political situation.

Sources: FY63 to FY93 are from WWF International as reported in Kull (1996); FY91–FY2012 were kindly provided by WWF Madagascar. Note that differences in accounting procedures result in inconsistent data between the two series (the 1962–1993 data, for example, only includes those funds passing through the Swiss headquarters of WWF International). Note also that fluctuations in foreign exchange rates strongly affect the figures.

This chapter revises and extends my 1996 article (which was based on interviews knocking on various doors in Antananarivo as a grad student in 1994). I’m thankful to Lisa Gezon and other participants in the Madagascar session at the 2007 AAG Conference for inspiring the idea to update that article. And to Ivan Scales for the venue. Great book, Ivan!